|

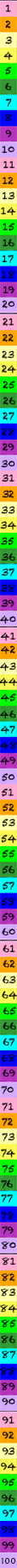

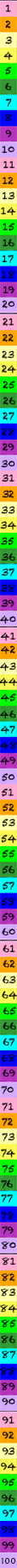

| 1 Original Alphabetical Menu 23

|

|

|

Menus

Menu 1 8 6:35

|

Menu 2 14.1 11:45

|

|

| Total 242,895 972 13:30 |

| Menu-Body 57% 1.5%, 1/1.76, 1/122 |

Numbered Chapters 1,944

Detailed Chapters 4 |

| Pages per chapter .5, 2.4, :25, 2:00 |

Views

|

Visitors

|

2 Wikipedia Functional Menu

| 1 Entertainment 9 |

| 2 Infrastructure 17 |

| 3 Monuments 7 |

| 4 Economy & Politics 16 |

| 5 Temples & Shrines 9 |

|

|

Functional from Wikipedia

1 Entertainment 9/200

| 1 Baths 23 |

| 2 Fields 21 |

| 3 Cliffs 1 |

| 4 Gardens 67 |

| 5 Groves 4 |

| 6 Lakes 8 |

| 7 Porticoes 56 |

| 8 Race Tracks 6 |

| 9 Theaters 14 |

|

2 Infrastructure 17/181

| 1 Aqueducts 15 |

| 2 Bridges 21 |

| 3 Cemeteries 6 |

| 4 Crematories 4 |

| 5 Docks 2 |

| 6 Fountains/Springs 16 |

| 7 Harbours. 7 |

| 8 Hospitals. 5 |

| 9 Military. 13 |

10 Mills 2  |

| 11 Mint 1 |

| 12 Prison. 1 |

| 13 Reservoirs. 2 |

| 14 Roads. 44 |

| 15 Waterways. 6 |

| 16 Wearhouses. 30 |

| 17 Walls & Gates. 6/38 |

|

3 Monuments 7/143

| 1 Arches 37 |

2 Columns. 12  |

3 Mausoleums. 4  |

| 4 Obolisks. 30 |

5 Statues. 47  |

| 6 Tombs 11 |

| 7 Towers 2 |

|

4 Economy & Politics 16/410

| 1 Apartments 3 |

| 2 Banks 1 |

| 3 Courts 7 |

| 4 Districs, Hills & Neighborhoods. 57 |

| 5 Executions. 1 |

| 6 Government Offices. 7 |

| 7 Libraries. 7 |

| 8 Markets. 11 |

| 9 Meeting Areas, "Basilicas". 12 |

| 10 Meeting Areas, "Fora". 29 |

| 11 Speaking Platforms "Rostrum". 7 |

| 12 Sheepfolds. 1 |

| 13 Slaughterhouses, "Macellum". 3 |

| 14 Stairs. 9 |

| 15 Trade Schools. 10 |

| 16 Wagon Depot. 1 |

| 17 Houses 244 |

|

5 Temples & Shrines 9/89

| 1 Aventine Hill. 6 |

| 2 Caelian Hill. 1 |

| 3 Capitoline Hill. 10 |

| 4 Campus Martius. 23 |

| 5 Esquiline Hill. 3 |

| 6 Forum Boarium. 6 |

| 7 Forum Holitorium. 5 |

8 Forum Romanum. 9  |

| 9 Imperial fora. 5 |

| 10 Palatine Hill. 10 |

| 11 Quirinal Hill. 6 |

| 12 Tiber Island. 3 |

| 13 Circus Maximus 1 |

| 14 Transtiberium 1 |

|

|

Organized by Subject.

1 Entertainment. 9/188

1 Baths. 23

|

|

2 Fields. 21

|

|

3 Cliffs.

|

|

|

5 Groves. 3

|

|

6 Lakes. 8

|

|

7 Porticoes. 56

|

|

8 Race Tracks. 6

|

|

9 Theaters. 14

|

|

|

|

2 Infrastructure. 17/211

1 Aqueducts. 15

|

|

|

3 Cemeteries. 6

|

|

4 Crematories. 2

|

|

5 Docks. 2

|

|

6 Fountains/Springs. 16

|

|

7 Harbours. 7

|

|

8 Hospitals. 5

|

|

9 Military. 13

|

|

|

11 Mint. 1

|

|

12 Prison. 1

|

|

13 Reservoirs. 2

|

|

Roads. 44

|

|

Waterways. 6

|

|

|

17 Walls & Gates. 6/38

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 Monuments. 7/143

1 Arches. 37

|

|

2 Columns. 12

|

7 Towers. 2

|

|

3 Mausoleums. 4

|

6 Tombs. 11

|

|

4 Obolisks. 30

1 Egyptian. 25

|

2 Roman. 5

|

|

|

5 Statues. 47

|

|

|

4 Economy & Politics. 16/410

|

2 Banks. 1

|

|

|

|

5 Executions. 1

|

|

6 Government Offices. 7 0 0

|

|

7 Libraries. 7

|

|

8 Markets. 11

|

|

9 Meeting Areas, "Basilicas". 12

|

|

Meeting Areas, "Fora". 29

|

|

11 Speaking Platforms

"Rostrum". 7

|

|

|

13 Slaughterhouses,

Macellum. 3

|

|

14 Stairs. 9

|

|

15 Trade Schools. 10

|

|

16 Houses. 244

1 Region 1 1

|

|

2 Region 2 8

|

|

3 Region 3 11

|

|

4 Region 4 11

|

|

5 Region 5 6

|

|

6 Region 6 3

|

|

7 Region 7 7

|

|

8 Region 8 0  |

|

9 Region 9 14

|

|

10 Region 0  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 Aventine 17

|

|

16 Caelian 19

|

|

17 Capitaline 9

|

|

18 Esquiline 44

|

|

19 Oppian Hill 1

|

|

20 Palantine (Region 10) 43

|

|

21 Pincian Hill 2

|

|

22 Quirinal 39

|

|

23 Viminal 7

|

|

24 Virinal 2

|

|

|

|

25 Temples & Shrines. 9/89

|

|

1 A

|

1 - 1 ACCA LARENTIA, ARA.

| Tomb of Acca Larentia in the Velabrum at the beginning of the Nova via, near the porta Romanula, beside which was an altar where sacrifices were offered by the pontifices on 23rd December. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 2 ADONAEA.

| Name found on a fragment of the Marble Plan which seems to belong to a large complex of buildings covering an area of about 1by 90 metres. Its location is not certainly known, though some authors place it at the east angle of the Palatine, in the large area known as Vigna Barberini, (see DOMUS AUGUSTIANA). On the other hand, on grounds of material, it appears that the fragment will not fit in at this part of the plan; and, if this is so, its site must be considered quite uncertain. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 3 ADONIDIS AULA.

| Hall or garden in the Flavian palace in which Domitian is said to have received Apollonius of Tyana, but nothing is known of its character. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 4 AEDES TENSARUM.

| mentioned only in one inscription, a military diploma; but probably the same building is referred to in another. This was on the Capitol and served to house the chariots, tensae, in which the statues of the gods were carried in processions. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 5 AEDICULA CAPRARIA.

| Mentioned in the Notitia among the monuments of the southern part of Region VII, but otherwise unknown (HJ 459). It may have stood in or near the VICUS CAPRARIUS. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 6 AEMILIANA.

| District outside the Servian wall in the southern part of the campus Martius, but whether near the Tiber, or near the via Flaminia just north of the porta Fontinalis, cannot be determined. It was ravaged by a great fire on 21st Oct., 38 A.D. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 7 AEOLIA.

| Balnea belonging to a certain Lupus, which are mentioned only by Martial. The name was perhaps derived from a picture of the island of Aeolus on the wall of the baths, or from its draughts, and in the latter case it may be simply a joke. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 8 AEQUIMELIUM.

| An open space on the lower part of the south-eastern slope of the Capitoline hill, above the vicus Iugarius. According to tradition this was the site of the house of Sp. Maelius that had been levelled with the ground by order of the senate, and the word itself was derived from his name. In Cicero's time it was the market-place for lambs used in household worship. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 9 AERARIUM SATURNI. (SATURNUS, AEDES).

The temple erected close to the original ara at the foot of the Capitoline and edge of the forum. It was the oldest temple of which the erection was recorded in the pontifical archives, but there was marked disagreement as to the exact date. One tradition ascribed its dedication to Tullus Hostilius; according to another it was begun by the last Tarquin. Elsewhere, however, its actual dedication is assigned to the magistrates of the first years of the republic, either to Titus Larcius in his dictatorship in 50, who also is said to have commenced building the temple in his second consulship in 498; or to Aulus Sempronius and M. Mamercus, the consuls of 497; or to Postumus Cominius, consul in 501 and 493, by vote of the senate. A different tradition seems to be preserved by Gellius Which Furius is referred to is not known, and this form of the tradition is probably valueless. The dedication of the temple may safely be assigned to the beginning of the republic.

In 174 B.C. a porticus was built along the clivus Capitolinus from the temple to the Capitolium. In 42 B.C. the temple was rebuilt by L. Munatius Plancus. It is mentioned incidentally in A.D., and at some time in the fourth century it was injured by fire and restored by vote of the senate, as recorded in the inscription on the architrave. It is represented on three fragments of the Marble Plan, and is mentioned in Reg.

Throughout the republic this temple contained the state treasury, the aerarium populi Romani or Saturni, in charge of the quaestors, and in it was a pair of scales to signify this function. Under the empire the same arrangement continued, but the aerarium Saturni now contained only that part of the public funds that was under the direction of the senate as distinguished from the fiscus of the emperors, and was administered by praefecti generally instead of quaestors; for the inscriptions relating to the aerarium, see DE i. 300; and for occurrences of aerarium populi romani or Saturni, Thes. ling. It is probable that only the money itself was kept in the temple, and that the offices of the treasury adjoined it, perhaps at the rear in the AREA SATURNI, until the building of the Tabularium in 78 B.C., when some at least of the records were probably transferred thither. Other public documents were affixed to the outer walls of the temple and adjacent columns.

On the gable of the temple were statues of Tritons with horses, and in the cella was a statue of Saturn, filled with oil and bound in wool, which was carried in triumphal processions. The day of dedication was the Saturnalia, 17th December. There are a few blocks of the podium of the original temple still remaining, and a drain below and in front is probably as early, in which case it and some similar drains close by are the earliest examples of the stone arch in Italy. There is no trace of any construction of an intermediate period, and the existing podium belongs to the temple of Plancus. It is constructed of walls of travertine and peperino, with concrete filling, and was covered with marble facing. It is 22.50 metres wide, about 40 long, and its front and east side rise very high above the forum because of the slope of the Capitoline hill. The temple was Ionic, hexastyle prostyle, with two columns on each side, not counting those at the angles. Of the superstructure eight columns of the pronaos remain, six in front and one on each side, together with the entablature, hitherto attributed to the period of the final restoration. It seems more likely that Fiechter is right in attributing the cornice to the Augustan period, on the analogy of several other cornices. The architrave blocks with the palmette frieze belowthem belong to the forum of Trajan,whence theywere removed for the fourth century restoration (ibid. 62-66). The front columns are of grey and those on the sides of red granite, while the entablature is of white marble. The columns are metres in height and 1.43 in diameter at the base; but in some of them the drums that form the shaft have been wrongly placed, so that the shaft does not taper regularly toward the top. The bases also are of three different kinds-Attic, and Corinthian with and without a plinth.

The steps of this temple were of peculiar form, on account of the closeness of the clivus Capitolinus and the sharp angle which it made in front of the temple, the main flight being only about one-third the width of the pronaos. It may be represented in a relief of the time of M. Aurelius and is certainly seen in one of those of the ROSTRA AUGUSTI. Considerably more of the temple was existing when Poggio first visited Rome in 1402 than was left in 1447, as we learn from his De varietate fortunae. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 10 AESCULAPIUS, AEDES.

| The temple of Aesculapius erected on the island in the Tiber soon after 291 B.C. In consequence of a pestilence in Rome in 293 an embassy was sent to Epidaurus in 292 to bring back the statue of the god Aesculapius. This embassy returned in 29bringing not the statue, but a serpent from Epidaurus that, on reaching Rome, abandoned the ship and swam to the island. According to another tradition the first temple was built extra urbem, the second in insult. The whole island was consecrated to Aesculapius, the temple built, and dedicated on 1st January. It was usually called aedes, but also templum, fanum, and Ἀσκλπιεῖα in Greek. Besides being the centre of the cult and of the sanatorium that developed on the island, this temple, being outside the pomerium, was also used as a place for the reception of foreign ambassadors, as those of Perseus in 170 B.C., and for such meetings as that between the senators and Gulussa. From a reference in Varro and some inscriptions it appears certain that the first temple was rebuilt or restored towards the end of the republic; perhaps when the pons Fabricius was built in 62 B.C. the first temple was decorated with frescoes. It is altogether probable that there was further restoration during the empire, perhaps under Antoninus Pius, but there is no direct evidence therefore.

There are no certain remains of this temple, but it probably occupied the site of the present church of S. Bartolomeo, and some of the columns of the nave probably belonged to the temple or its porticus. A considerable number of inscriptions relating to the temple or to votive offerings in it have been found in the vicinity, and many terracottas, most of which have been dispersed. A signum Aesculapii is mentioned as standing near the temple in the time of Augustus, but such statues of the god were undoubtedly numerous in and around the temple, as well as elsewhere in Rome. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 11 AESCULETUM.

| A grove of oaks in the campus Martius, in which the assembly met in 287 B.C. to pass the Hortensian laws. If the VICUA AESC(U)LETI took its name from the grove, it must have been a little north of the. modern ponte Garibaldi. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 12 AGER L. PETILII.

| Property lying sub Ianiculo, but otherwise unknown, where the tomb and books of Numa were said to have been found in 181 B.C. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 13 AGER TURAX. (CAMPUS TIBERINUS).

| Another name for the CAMPUS MARTIUS according to Gellius, who, with Pliny. It has also been explained as that part of the campus Martius that borders the river from the island northward and identified with the CAMPUS MINOR of Catullus, and the ἄλλο πέδιον of Strabo. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 14 AGER VATICANUS. (VATICANUS AGER).

| the district on the right bank of the Tiber, between its lower reaches and the more restricted Veientine territory. Its fertility is spoken of slightingly by Cicero, its wines are frequently derided by Martial, and references to farms or estates are very few. This name continued long in use, for it occurs in Solinus, and in Gellius, who gives two current explanations of the name.

It is probable that the adjective form, Vaticanus, is derived from some substantive, perhaps Vaticanum, or from the early Etruscan name of some settlement, like Vatica or Vaticum, of which all other traces have vanished, except possibly the cognomen Vaticanus which is found twice in the consular Fasti in 455 and 451 B.C.

( VATICANI MONTES

without much doubt a general designation for the hills in the ager Vaticanus, but used, in its only occurrence in litera- ture, of the long ridge from the Janiculum to the modern Monte Mario. Here campus Vaticanus must be used of the whole district between Monte Mario and the Tiber, known in modern times until very recently as the Prati di Castello.

( VATICANUS MONS

in the singular could be used of any one of the montes within the limits of the ager Vaticanus. It occurs ian Horace, where it means the Janiculum, and in Juvenal, where it is more general, as the clay pits are scattered all along this ridge. Festus' Vaticanus collis is to be explained as a mere variant of mons, introduced simply for the sake of the etymology. There is no evidence that Vaticanus mons was a specific name for any one part of the ridge during the classical period. It was in consequence of the gradual restriction of Vaticanum to the area occupied by the CIRCUS GAI ET NERONIS , and the identification of this site as the burial place of S. Peter, that Vaticanus mons became localised in its mediaeval and modern sense. With this new importance in Christian Rome, it took its place among the seven hills (Not. app.).

( VATICANA VALLIS

used once, by Tacitus, for the site of the circus Gai et Neronis, or, if not for its exact site, for the entrance to the depression of the modern Vicolo del Gelsomino, just south-west of the area occupied by the circus proper.

VATICANUM

the substantive, either an original place name or the neuter of the adjective , which was used first to designate, in whole or in part, the level district between the Janiculum-Monte Mario ridge and the Tiber, being more or less equivalent to Cicero's campus Vaticanus, and extending south, probably to the city limits proper. Part at least of this district was regarded as unhealthy; thrice tombs are mentioned that probably stood along the line of the modern Borghi; and it contained a recognised pauper element in its population.

With the building of the circus Gai et Neronis, which was also called circus Vaticanus, increased importance was given to this particular area, and Vaticanum then came to be used of the circus itself, as well as of the whole district.

Another application of the name Vaticanum seems to have been to the shrine of the Magna Mater, whose cult was established close to the circus, if we may judge from an inscription found at Lyon. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 15 AGER VERANUS.

| The name given in the middle ages to the site occupied by the catacombs of S. Cyriaca and later by the church of S. Lorenzo and the modern cemetery, campo Verano; this district probably took its name from its owner in classical times. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 16 AGGER. (MURUS SERII TULLII.)

| The wall ascribed by tradition to the sixth of the kings of Rome, perhaps in completion of work already begun by Tarquinius Priscus.

There is considerable discord in the tradition as to which hills were added to the city by which kings; but the statement that Servius Tullius added the Esquiline and the Viminal is consistent with the facts

It is probable that the original settlements on the Palatine, Capitol, Quirinal, etc., had no stone walls, but relied on natural features or sometimes on earthworks, e.g. MURUS TERREUS CARINARUM .

There are remains of a wall in smallish blocks of grey tufa (cappellaccio) at various points on the line of the later enceinte, which are usually assigned to the original wall of Servius Tullius of the sixth century B.C.

The blocks employed are from 0.20 to 0.30 metre high, 0.55 to 0.66 wide and 0.75 to 0.90 long. The most important sections of this wall are to be seen:

(a) at the head of the Via delle Finanze, where the Villa Spithoever once stood. This fine section of it (Ill. 36), some 35 metres long, was discovered in 1907, but a modern street has been run through the middle of it; while other pieces were discovered to the south-west in the garden of the Ministry of Agriculture. Other similar remains appear to have been found near S. Susanna and S. Maria della Vittoria in the seventeenth century, and some of it was still visible in 1867 (Jord. k), though not mentioned in other lists.

(b) in the Piazza dei Cinquecento, opposite the station.

(c) at the south-west angle of the Palatine.

(d) on the north side of the Capitol, under the retaining wall in front of the German Embassy above the Vicolo della Rupe Tarpea; omitted by Jord. i. I. 207, regarding it as a part of the substructions of the area of the temple of Jupiter. The two probably coincided at this point.

(e) in the garden of the Palazzo Colonna at the west end of the Quirinal.

Of these fragments of wall, (a) and (e) undoubtedly belonged to the outer line, while (b) was the retaining wall at the back of the agger, which, no doubt, existed from the first. Of (d) we can say nothing certain, and (c) may belong either to the Palatine or to the Servian enceinte.

To ascribe them to the wall of the city of the Four Regions is impossible, as (a) and (b) would both then be excluded ; and it is very doubtful if this city ever had a wall of its own.

Frank maintains (TF 117, 18) that the battering back of the courses, the use of anathyrosis and the presence of walls of Grotta Oscura tufa of the fourth century B.C. in conjunction with these fragments, are sufficient to make it probable that they should also be assigned to the same period.

It seems, however, more likely that the cappellaccio wall should, as far as our knowledge goes at present, be attributed to the sixth century B.C.

The line of wall (text fig. began at the Tiber, crossed the low ground to the south-west corner of the Capitol, ran north-east along the edge of the cliffs of this hill and the Quirinal, until it almost reached the head of the valley between the Quirinal and the Pincian (Collis Hortorum). Then it ran southwards across the tableland of the Esquiline, crossed the valley between the mons Oppius and the Caelian, followed the cliffs on the south-east and south of this hill, then probably followed the south-west side of the Palatine, and thence ran south of the forum Boarium to the Tiber again.

It is possible that we should attribute to the enceinte of this period an arch with a span of Roman feet (3.30 metres), found in 1885 forty metres south of S. Maria in Cosmedin and constructed of voussoirs of cappellaccio. Its left (south- east) side joined a wall of the same material, which ran into the hill. A paved road passed through it, which was taken to be the CLIVUS PUBLICIUS , but it had been blocked up by a wall in opus reticulatum. Borsari (BC 1888, 21) maintained that it was the PORTA TRIGEMINA , but it is most improbable that the road passing through it would have been blocked up at so early a period as the second century A.D. Nor, as Hulsen points out (Mitt. 1889, 260), does its position suit what we know of the line of the Servian wall. Frank (AJA cit.) attributed it to the wall of the ' City of the four regions,' omitting the Aventine; but later, apparently forgetting the information he had obtained from Lanciani (who stated that, as far as he could remember, the material was cappellaccio), he assumed that the material was Fidenae tufa, which is full of scoriae, and that it belonged to the Palatine wall of the fourth century B.C. (TF 95, 96).

It is probable that a consequence of the Etruscan victory over the Romans at the beginning of the Republic was the dismantling of the fortifications of the city. A treaty such as that concluded with Porsena, in which the Romans were forbidden to carry weapons of iron, would doubtless have included this: and the success of the Gallic invasion can hardly be understood Prof. Hulsen has kindly communicated this view to me, and I fully agree with it. unless Rome was an open town.

As the result of the Gallic invasion, the whole enceinte was enormously reinforced and strengthened, the original line, however, being for the most part, if not entirely, retained.

To the construction of this wall the following passages have generally been referred: (377 B.C.).

(353 B.C.).

It is natural that so great a work as this should have taken a considerable number of years to build.

To this reconstruction belongs all the masonry of larger blocks. Frank remarks that, though the majority of the blocks measure 58-61 cm. high, there is a good deal of irregularity even on the outer face, where he has noted measures as low as 51 cm. and as high as 64, while on the inside, where the agger conceals the blocks, the measurements vary from 40 to 68 cm. The material, however, is entirely Grotta Oscura tufa ; and this seems an even clearer test than that of measurement. The quarry marks too (Ann. d. Inst. 1876, 72; Richter, Antike Steinmetzzeichen) cannot be referred to an earlier period than the fourth century B.C., and, as the stone came from the Grotta Oscura quarries, in the territory of Veii, soon after the fall of that town, it is suggested that they may be Etruscan rather than Roman. In this enceinte the Aventine was for the first time probably included; and a fine piece of wall belonging to it may be seen in the depression between the greater and the lesser Aventine in the Via di Porta S. Paolo. As this meant an increased weakness from the defensive point of view, it was quite natural that the builders of the original wall should have left it and the valley of the circus Maximus out of their scheme. The continuation has been cleared to the north-west of it on the greater Aventine and is almost entirely of Grotta Oscura tufa.

From the porta Collina to the porta Esquilina, where the Servian wall, instead of following the edge of the hill, was obliged to cross the tableland at the base of the Quirinal, Viminal and Esquiline, it was strengthened by a great mound, described by Dionysius as seven stadia in length and 50 feet thick, with a ditch in front of it 30 Roman feet deep and 100 wide. The porta Viminalis was the only gate which passed through this part of the fortifications, which were further strengthened by towers. With a part of the outer wall of the agger near by, it is still preserved in the railway station. Another piece may be seen in the Piazza Manfredo Fanti.

Other parts of the enceinte were fortified in the same way; but this was the agger par excellence, and long after its function had ceased it is spoken of by ancient authors as a prominent feature, and it survived as a local name in the form Superage as late as 105from which the church took the name of Superagius, and even in 1527.

Many other portions of the wall are preserved, but are too insignificant to deserve separate mention, with the exception of an arch on the slope of the Quirinal, in the modern Palazzo Antonelli, which is only 1.05 metres in span, and therefore not a city gate (87 B.C.). For the remains on the Capitol, see ARX.

We cannot admit either that the Palatine was still a separate community when the wall of blocks 2 feet high was built on its north-west side or that this wall was part of a larger enceinte; and we must therefore suppose that it continued to be separately fortified as late as the fourth century B.C. as an additional internal citadel or fort. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 17 AGONUS.

| According to Festus this was the earlier name of the collis Quirinalis, derived from agere 'to offer sacrifice,' but this was probably simply an invention of the antiquarians, where an even more absurd suggestion is made, that agonus=mons. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 18 AGRI NOVI. (CAMPUS ESQUILINUS).

| the name in use during the last period of the republic and early empire for that part of the Esquiline plateau that lay outside the porta Esquilina. What its exact limits were, either then or earlier, is not known, but it is said to have been situated north of the via Labicana, and it probably included part of the present Piazza Vittorio Emanuele and the district immediately north of it. It formed a part of what had been the early Esquiline necropolis, a place of burial for prominent Romans as well as for the poor, but it had been reclaimed at the beginning of the Augustan period and was used as a park. It is referred to as Agri novi by Prop. Executions also took place here. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 19 AGRIPPAE TEMPLUM. (PANTHEON).

| a temple which, with the thermae, Stagnum and Euripus, made up the remarkable group of buildings which Agrippa erected in the campus Martius. According to the inscription on the frieze of the pronaos. This passage is not altogether clear, but it seems probable that the temple was built for the glorification of the gens Iulia, and that it was dedicated in particular to Mars and Venus, the most prominent among the ancestral deities of that family. In the ears of the statue of Venus hung earrings made of the pieces of Cleopatra's pearls. Whether the name refers to the number of deities honoured in the temple, or means 'very holy', is uncertain: but Mommsen's conjecture that the seven niches were occupied by the seven planetary deities is attractive, and Hilsen is now in favour of it. There is no probability in Cassius Dio's second explanation.

In the pronaos of Agrippa's building were statues of himself and Augustus, and on the gable were sculptured ornaments of note. The decoration was done by Diogenes of Athens, and Pliny goes on to say. The position of these Caryatides has been much discussed, but is quite uncertain.

The Pantheon of Agrippa was burned in 80 A.D. and restored by Domitian. Again, in the reign of Trajan, it was struck by lightning and burned. The restoration by Hadrian carried out after 126 was in fact an entirely new construction, for even the foundations of the existing building date from that time. The inscription was probably placed by Hadrian in accordance with his well-known principle in such cases. The restoration ascribed to Antoninus Pius may refer only to the completion of Hadrian's building. Finally, a restoration by Severus and Caracalla in 202 A.D. is recorded in the lower inscription on the architrave. In January, 59 A.D., the Arval Brethren met in the Pantheon; Hadrian held court in his restored edifice; Ammianus speaks of it as one of the wonders of Rome; and it is mentioned in Reg.

For a library situated in or near the Pantheon, see THERMAE AGRIPPAE; THERMAE NERONIANAE.

The building faces due north; it consists of a huge rotunda preceded by a pronaos. The former is a drum of brick-faced concrete, in which numerous brickstamps of the time of Hadrian have been found. which is 6.20 metres thick; the structure of it is most complex and well thought out. On the ground level the amount of solid wall is lessened by seven large niches, alternately trapezoidal and curved (the place of one of the latter being taken by the entrance, which faces due north), and by eight void spaces in the masses of masonry between them, while in the upper story there are chambers above the niches, also reached by an external gallery supported by the middle of the three cornices which ran round the dome. In front of these masses are rectangular projections decorated with columns and pediments alternately triangular and curved, which have been converted into altars. The pavement is composed of slabs of granite, porphyry and coloured marbles; and so is the facing of the walls of the drum, which is, however, only preserved as far as the entablature supported by the columns and pilasters, the facing of the attic having been removed in 1747. The ceiling of the dome is coffered, and was originally gilded ; in the top of it is a circular opening surrounded by a cornice in bronze, 9 metres in diameter, through which light is admitted. The height from it to the pavement is 43.20 metres (144 feet), the same as the inner diameter of the drum. The walls are built of brick-faced concrete, with a complicated system of relieving arches, corresponding to the chambers in the drum, which extend as far as the second row of coffers of the dome; the method of construction of the upper portion is somewhat uncertain (the existence of ribs cannot be proved), but is probably of horizontal courses of bricks gradually inclined inwards. Pumice stone is used in the core for the sake of increased lightness.

The ancient bronze doors are still preserved, though they were repaired in the sixteenth century. The pronaos is rectangular, 34 metres wide and 13.60 deep, and has three rows of Corinthian columns, eight of grey granite in the front row and four of red granite in each of the second and third. Of those which were missing at the east end, as they were already absent earlier, the corner column was replaced by Urban VIII with a column of red granite, and the other two by Alexander VII, with grey columns from the thermae Alexandrinae. The columns support a triangular pediment, in the field of which were bronze decorations; in the frieze is the inscription of Agrippa; and the roof of the portico behind was supported by bronze trusses. This portico was not built after the rotunda, as recent investigations by Colini and Gismondi have shown, and the capitals of its columns are exactly like those of the interior, though the entasis of the columns differs. In front of it was an open space surrounded by colonnades. The hall at the back belongs also to Hadrian's time, and so do the constructions on the east in their first form. The exterior of the drum was therefore hardly seen in ancient times.

The podium of the earlier structure, built by Agrippa, lies about 2.50 metres below the pavement of the later portico; it was rectangular, 43.76 metres wide and 19.82 deep, and faced south, so that the front line of columns of the latter rests on its back wall, while the position of the doorways of the two buildings almost coincides. To the south of the earlier building was a pronaos 21.26 metres wide, so that the plan was similar to that of the temple of Concord. At 2.metres below the pavement of the rotunda there was an earlier marble pavement, which probably belonged to an open area in front of the earlier structure; but a marble pavement of an intermediate period (perhaps that of Domitian) was also found actually above this earlier structure, but below the marble pavement of the pronaos.

The restoration of Severus and Caracalla has been already mentioned; but after it, except for the account by Ammianus Marcellinus, already cited, of Constantius' visit to it, we hear nothing 9 of its history until in 609 Boniface IV dedicated the building as the church of S. Maria ad Martyres. Constantius II removed the bronze tiles in 663; and it was only Gregory III who placed a lead roof over it. That the pine-cone of the Vatican came from the Pantheon is a mediaeval fable; it was a fountain perhaps connected with the SERAPEUM .

The description of it by Magister Gregorius in the twelfth century is interesting, especially for the mention of the sarcophagi, baths and figures which stood in front of the portico. A porphyry urn, added by Leo X, now serves as the sarcophagus of Clement XII in the Lateran. For its mediaeval decoration.

Martin V repaired the lead roof and Nicholas V did the same. Raphael is among the most illustrious of the worthies of the Renaissance who are buried here.

The removal of the roof trusses of the portico by Urban VIII gave rise to the famous pasquinade. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 20 AIUS LOCUTIUS, ARA.

| an altar erected in 390 B.C. by order of the senate at the north corner of the Palatine in infima Nova via, opposite the grove of Vesta. It was dedicated to the deus indiges, Aius Locutius, the speaking voice. Tradition agreed in relating that in 391 a plebeian, M. Caedicius, heard at night at this point a voice that warned the Romans of the invasion of the Gauls. No attention was paid to this warning until after the event, when the altar was built in expiation. Besides ara, this altar is also referred to as saceUum and templum, but there is no doubt that it was an enclosed altar in the open air. This altar has no connection with that found on the south-west slope of the Palatine near the Velabrum, dedicated sive deo sive deivae. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 21 ALBIONARUM LUCUS.

| A grove somewhere on the right bank of the Tiber, consecrated to the Albionae, who were probably connected with the protection of the fields. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 22 ALMO.

| The modern Acquataccio, a stream that rises between the via Latina and the via Appia, receives the water of the modern Fosso del- I'Acqua Santa, flows north-west and west for six kilometres and empties into the Tiber about one kilometre south of the porta Ostiensis. It formed the southern boundary of Region I, and in it the ceremony of bathing the image of Cybele took place annually on 27th March. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 23 ALTA SEMITA.

| The name given in the Regionary Catalogue to the sixth region of Augustus. This lay between the imperial fora, the east boundary of Region VII, and the north-west boundary of Region IV, and included the Viminal, the Quirinal, the valley between the Quirinal and the Pincian, and the lower slope of the latter hill. This region took its name from that of its principal street, the Alta Semita, which ran north-east along the ridge of the Quirinal to the porta Collina, corresponding with the modern Via del Quirinale and Via Venti Settembre from the Piazza del Quirinale eastward. The north-eastern part of this street was probably called VICUS PORTAE COLLINAE , if we may infer this from an inscription found near S. Susanna. The ancient pavement lies at an average depth of 1.83 metres below the present level. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 24 AMICITIA, ARA.

| An altar erected in 28 A.D. by order of the senate, dedicated to the amicitia of Tiberius, probably as illustrated in the case of Sejanus. Its site is entirely unknown. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 25 AMPHITHEATRUM.

| a form of building that originated, apparently, in Campania, but was developed in Rome after the end of the republic. It was widely diffused throughout Italy, and has always been regarded as a distinctly Roman structure. It was intended primarily for gladiatorial contests and venationes, which had previously taken place in the forum. Around the open area of the forum temporary seats had been erected, forming an irregular ellipse. This was the reason for the shape of the amphitheatre, and for the name itself which means 'having seats on all sides.' This word, however, does not occur before the Augustan era, and was at first applied to the circus also; in the inscription on the building at Pompeii we find spectacula used.

The amphitheatres erected in the city of Rome itself were the following: |

|

|

|

|

1 - 26 AMPHITHEATRUM CALIGULAE.

| begun by Caligula near the Saepta, but left unfinished, and abandoned by Claudius. See AQUA VIRGO. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 27 AMPHITHEATRUM CASTRENSE.

This name, found only in the Regionary Catalogue, belongs without doubt to the structure of which some remains are still visible, near the SESSORIUM . Castrense is to be explained as meaning' belonging to the imperial court,' and the brickwork is that of the time of Trajan, who was especially fond of buildings of this kind. It is possible that this is the θέατρονmentioned by Pausanias as one of the most important buildings of Trajan.

It was elliptical in form, with axes 88.5 and 78 metres in length, and constructed entirely of brick and brick-faced concrete. The exterior wall consisted of three stories of open arcades, adorned with pilasters and Corinthian capitals. When the Aurelian wall was built, the amphitheatre was utilized as a part of the line of fortification, the wall being joined to it in the middle of the east and west sides. The outer half of the building was thus made a projecting bastion, and the open arcades of the exterior were walled up, the ground level outside being at the same time lowered. The inner half was evidently pulled down, so that little use can have been made of the edifice at that time.

Drawings of the sixteenth century represent all three stories, but since that time the upper one has entirely disappeared and all but a few fragments of the second. The cavea and the wall of the arena have also been destroyed, so that the remaining portion consists of the walled-up arcades of the lowest story. See Ill. which shows its condition in 1615; ASA 96.

Rivoira puts it in the first half of the third century.

|

|

|

|

|

1 - 28 AMPHITHEATRUM FLAVIUM.

| ordinarily known as the Colosseum, built by Vespasian, in the depression between the Velia, the Esquiline and the Caelian, a site previously occupied by the stagnum of Nero's domus Aurea. Vespasian carried the structure to the top of the second arcade of the outer wall and of the maenianum secundum of the cavea , and dedicated it before his death in 79 A.D. Titus added the third and fourth stories2 (ib.), and celebrated the dedication of the enlarged building in 80 with magnificent games that lasted one hundred days. Domitian is said to have completed the building ad clipea which probably refers to the bronze shields that were placed directly beneath the uppermost cornice and to additions on the inside.

There are indications of changes or additions by Nerva and Trajan, and it was restored by Antoninus Pius. In 2it was struck by lightning, and so seriously damaged that no more gladiatorial combats could be held in the building until 222-223, when the repairs begun by Elagabalus were at least partially completed by Alexander Severus, although they seem to have continued into the reign of Gordianus III. In 250 the building was presumably restored by Decius, after a fire caused by another stroke of lightning. It was injured by the earthquake of 442, and restorations by different officials are recorded in the years immediately succeeding, and again in 470. Some of the inscriptions set up on the former occasion in honour of Theodosius II and Valentinian III were cut on marble blocks which had originally served as seats. Repairs were made after another earthquake by the prefect Basilius, who was probably consul in 508, and finally by Eutharich, the son-in-law of Theodoric, in preparation for the last recorded venationes, which took place in 523. The last gladiatorial combats occurred in 404.

The Colosseum was injured by an earthquake in the pontificate of Leo IV (in 847). In the eleventh and twelfth centuries houses and isolated 'cryptae ' within the Colosseum are frequently mentioned in documents of the archives of S. Maria Nova, as though it were already in ruins. Gradual destruction continued until the eighteenth century, while the work of restoration has gone on intermittently since the beginning of the nineteenth. The north side of the outer wall is standing, comprising the arches numbered xxiii to LIV, with that part of the building which is between it and the inner wall supporting the colonnade, and practically the whole skeleton of the structure between this inner wall and the arena-that is, the encircling and radiating walls on which the cavea with its marble seats rested. The marble seats and lining of the cavea, together with everything in the nature of decoration,' have disappeared.

The amphitheatre is elliptical in form. Its main axis, running north-west-south-east, is 188 metres in length, and its minor axis 156. The exterior is constructed of large blocks of travertine-a fact that contributed greatly to the astonishment of Constantius; and in the interior Vespasian erected a skeleton of travertine blocks where the greatest pressure had to be resisted, which was not carried higher than the second story. The remainder of the inner walls are of blocks of and of concrete, with and without brick facing, the former being used where there was more pressure. Some tufa and sperone is also employed in the lower part of the inner walls. The outer wall, or facade, is 48.50 metres high, and stands upon a stylobate, which is raised two steps a pavement of travertine. This pavement is 17.50 metres wide, extended around the whole building. Its outer edge is marked by a row of stone cippi-five of which on the east side are in situ with holes cut on the inner side to hold the ends of barriers connecting these posts with the wall of the building. The outer wall itself is divided into four stories, of which the lower three consist of rows of open arcades, a style of architecture borrowed from the theatre of Marcellus. The arches of the lower arcade are 7.05 metres high and 4.20 wide; the pillars between them are 2.40 metres wide and 2.70 deep. In front of these pillars are engaged columns of the Doric order, which support an entablature 2.35 metres high, but without the distinguishing characteristics of this order. There were eighty arches in the lower arcade, of which the four at the ends of the two axes formed the main entrances to the amphitheatre, and were unnumbered. The remaining seventy-six were numbered, the numbers being cut on the facade just beneath the architrave. Above the entablature is an attic of the same height, with projections above the columns, which serve as pedestals for the engaged columns of the second arcade. This arcade has the same dimensions as the lowest, except that the arches are only 6.45 metres high. The half-columns are of the Ionic order, and in turn support an entablature 2.metres in height, but not in perfect Ionic style. Above this is a second attic, 1.95 metres high, on which the columns of the third arcade rest. The last is of the Corinthian order, and its arches are 6.40 metres high. Above this is a third entablature and attic. In each of the second and third arcades was a statue.

The attic above the third arcade is 2.metres high, and is pierced by small rectangular windows over every second arch. On it rests the upper division of the wall, which is solid and adorned with flat Corinthian pilasters in place of the half-columns of the lower arcades, but shows numerous traces of rude reconstruction in the third century. Above the pilasters is an entablature, and between every second pair of pilasters is a window cut through the wall-. Above these openings is a row of consoles-three between each pair of pilasters. In these consoles are sockets for the masts which projected upward through corresponding holes in the cornice and supported the awnings (velaria) that protected the cavea.

Within this outer wall, at a distance of 5.80 metres, is a second wall with corresponding arches; and 4.50 metres inside of this a third which divides the building into two main sections. On the lower floor, between these three walls, are two lofty arched corridors or ambulatories, encircling the entire building; on the second floor, two corridors like those below, except that the inner one is divided into two, an upper and a lower; and on the third floor two more. In the inner corridor on the second floor, and in both on the third, are flights of steps very ingeniously arranged, which lead to the topmost story, and afford access to the upper part of the second tier of seats. Within the innermost of the three walls just mentioned are other walls parallel to it, and radiating walls, struck from certain points within the oval and perpendicular to its circumference. These radiating walls correspond in number to the piers of the lower arcade, and are divided into three parts, so as to leave room for two more corridors round the building. This system of radiating walls supported the sloping floor (cavea) on which the rows of marble seats (gradus) were placed. Underneath, in corridors and arches, are other flights of steps which lead to all parts of the cavea, through openings called vomitoria. They are arranged in fours.

The arena itself is elliptical, the major axis being 86 metres long and the minor 54. All round the arena was a fence, built to protect the spectators from the attacks of the wild beasts, and behind it a narrow passage paved with marble. Above this passage was the podium, a platform raised about 4 metres above the arena, on which were placed the marble chairs of the most distinguished spectators. These chairs seem to have been assigned to corporations and officials, not to individuals as such, until the time of Constantine, when they began to be assigned to families an rarely to individuals. This continued until the fifth century, when possession by individuals became more common. The names of these various owners were cut in the pavement of the podium, on the seats themselves, and above the cornice, and many of these inscriptions have been preserved. When a seat passed from one owner to another, the old name was erased and a new one substituted. The front of the podium was protected by a bronze balustrade.

From the podium the cavea sloped upward as far as the innermost of the three walls described above. It was divided into sections (maeniana) by curved passages and low walls; the lower section (maenianum primum) contained about twenty rows of seats (gradus) and the upper section (maenianum secundum), further subdivided into maenianum superius and inferius, about sixteen. These maeniana were also divided into cunei, or wedge-shaped sections, by the steps and aisles from the vomitoria. The gradus were covered with marble, and when assigned to particular corporations the name was cut on the stone. Eleven such inscriptions have been found, and indicateD that space was assigned by measure and not according to the number of persons (cf. the assignment to the Fratres Arvales, CILvi. 2059 =3236. Each individual seat could, however, be exactly designated by its gradus, cuneus and number, as was done elsewhere.

Behind the maenianum secundum the wall rose to a height of 5 metreS above the cavea, and was pierced with doors and windows communicating with the corridor behind. On this wall was a Corinthian colonnade, which together with the outer wall, supported a flat roof. The columns were of cipollino and granite, dating from the Flavian period.7Behind them, protected by the roof, was the maenianum summum in ligneis, which contained wooden seats for women. These seats were approached from above by a vaulted corridor, lighted by the windows between the pilasters (p. 8) as has been supposed by Hulsen. On the roof was standing room for the pullati, or poorest classes of the population.8 The modern terrace is lower than this roof was, and about at the level of the floor of the corridor behind the wooden seats. Of the four principal entrances, those at the north and south ends of the minor axis were for the imperial family, and the arches here were wider and more highly ornamented than the rest. The entrance on the north seems to have been connected with the Esquiline by a porticus. A wide passage led directly from this entrance to the imperial box on the podium. A corresponding box on the opposite side of the podium was probably reserved for the praefectus urbi. The entrances at the ends of the major axis led directly into the arena.

The floor of the arena, which must have been of wood, rested on lofty substructures, consisting of walls, some of which follow the curve of the building, while others are parallel to the major axis. They stand on a brick pavement and are from 5.50 to 6.08 metres high. These substructures are entered by subterranean passages, on the lines of the major and minor axes. Another such passage, resembling a cryptoporticus, starts from a raised substructure, projecting a little beyond the line of the podium, not far to the east of the state entrance on the south side, and leads to the buildings of Claudius on the Caelian, and is usually ascribed to Commodus. In the substructures are traces of dens for wild beasts, elevators, and mechanical appliances of various sorts, and provision was made for the drainage of the water which flows so abundantly into this hollow and which was carried off in a sewer connecting with that running under the via S. Gregorio. The masonry of the substructures dates from the first century to the end of the fifth.

The statement in the Regionary Catalogue (Reg. III), that the amphitheatre had 87,000 loca, cannot refer to persons but pedes, and even so, it is probably incorrect, for the total seating capacity cannot have exceeded forty-five thousand, with standing room on the roof for about five thousand more.

Nine published fragments of the Marble Plan represent parts of the amphitheatre, and there are a few others of little importance and uncertain position. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 29 AMPHITHEATRUM NERONIS.

| A wooden structure, erected by Nero on the site of that of STATILIUS TAURUS . It was finished in a year, but is spoken of by Tacitus in such a way as to imply that it was not a remarkable building. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 30 AMPHITHEATRUM STATILII TAURI.

| an amphitheatre built of stone by L. Statilius Taurus in 29 B.C., probably in the southern part of the campus Martius. It was burned in 64 A.D., and Nero built another on the same site. Caligula is said to have looked upon it with scorn, perhaps on account of its small size. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 31 ANAGLYPHA TRAIANI. (ROSTRA).

| the original platform from which the orators addressed the people. It took its name from the beaks of the ships captured from the people of Antium in 338 B.C. with which it was decorated. It was situated on the south side of the Comitium in front of the Curia Hostilia in close connection with the SEPULCRUM ROMULI , i.e. between the Comitium and forum, so that the speaker could address the people assembled in either. It is spoken of as the most prominent place in the forum. It was consecrated as a templum, and on it were placed statues of famous men in such numbers that at times they had to be removed to make way for others; while the COLUMNA ROSTRATA C. DUILII stood on or close by it.

The name rostra vetera is only used in Suet. Aug. 100; where it refers to the rostra transferred by Caesar to the north-west end of the forum in contradistinction to the rostra at the temple of Divus Iulius; though it is commonly and conveniently used to signify the republican rostra in contradistinction to the rostra of Caesar.

Excavations in the Comitium have brought to light remains which must be attributed to the republican rostra, though much doubt attaches to their exact interpretation. 'It would appear that about the middle of the fifth century B.C. the Comitium was separated from the forum by a low platform, upon which stood the archaic cippus, the cone, and probably an earlier monument, represented by the existing sacellum. After the fire that followed the Gallic invasion, the first platform was replaced by a higher, to which a straight flight of steps led up from the second level of the COMITIUM . A wall, 3 metres in front of these steps, perhaps formed part of the rostra. In this platform was an irregular space, bounded by walls on each side, enclosing the monuments in question. Whether remains of the platform of this period exist, or whether the cappellaccio slabs which have been attributed to it are really the bedding for the tufa slabs of the next period, is a moot point. According to another theory, a kerb along the northern edge of the cappellaccio pavement in front of the basilica Aemilia marked the front line of the original rostra.

There is no trace of any alteration in the rostra corresponding with the third level of the Comitium; but in correspondence with the fourth we have a reconstruction of the rostra on a new plan. 'Its remains consist (I) of a curved structure of large blocks of Monte Verde tufa, forming two steps about 35 cm. high, which rested on a foundation of cappellaccio (grey) tufa cm. high; ( of a low corridor or canalis, 1 metre wide and about 75 cm. high, parallel to the curved line of the steps and about 9 metres from them; ( of a platform, or suggestus, to the west of the niger lapis, and ( of a row of shafts, or pozzi, running east and west, about 6.75 metres distant from the platform. The portion of the platform ... .on which the curved flight of steps rested, lay about one metre above the floor of the Comitium.' It has a fine pavement of Monte Verde tufa, along the front of which runs a raised kerb. According to one view these monuments are attributable to the period of Sulla. Whether the 'Tomb of Romulus ' was hidden from view at this period or later, is uncertain.

The curved front of the rostra, as represented by the canalis with the beaks of ships with which it was adorned, is held to be represented in a coin of 45 B.C. of Lollius Palikanus. The arcade at the back of the rostra Augusti, which Boni has called the rostra Caesaris, belongs to the time of Sulla, and is simply a low viaduct to support the CLIVUS CAPITOLINUS and a street branching off from it. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 32 ANIO NOVUS.

| an aqueduct, which, like the aqua Claudia, was begun by Caligula in 38 A.D. and completed in 52 A.D. by Claudius, who dedicated them both on 1st August. The cost of the two was 350,000,000 sesterces, or £3,500,000 sterling. Originally the water was taken from the river Anio at the forty-second mile of the via Sublacensis; but, as the water was apt to be turbid, Trajan made use of the two uppermost of the three lakes formed by Nero for the adornment of his villa at Subiaco-the Simbruina stagna of Tac. Ann. xiv. 22, thus lengthening the aqueduct to 58 miles 700 paces. The length of 62 miles given to the original aqueduct in the inscription of Claudius on the PORTA MAIOR must be an error for 52; for an unsuccessful attempt to explain it otherwise see Mel. 1906. We have a record of repairs to it in an inscription of 381 A.D., but it is uncertain what part of it is meant. Its volume at the intake was 4,738 quinariae, or 196,627 cubic metres in 24 hours. Its course outside the city cannot be described here.

From its piscina (or filtering tank) near the seventh milestone of the via Latina it was carried on the lofty arches of the aqua Claudia, in a channel immediately superposed on the latter; and it was the highest in level of all the aqueducts that came into the city.

These arches ended behind the HORTI PALLANTIANI , the former Vigna Belardi, where the terminal piscina of these two aqueducts was situated.

Like the Claudia, the Anio Novus supplied the highest parts of the city. Before the reforms introduced by Frontinus, it was freely used to supply the deficiencies (largely due to dishonesty) of other aqueducts, and, being turbid, rendered them impure. The removal of its defects, however, is said to have rendered it equal to the Marcia. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 33 ANIO VETUS.

an aqueduct commenced in 272 B.C., which took its supply from the river Anio, at a point opposite Vicovaro, the ancient Varia, 8 miles from Tibur. The meaning of the phrase in Frontinus i. 6, is therefore quite uncertain. He gives it a length of 43,000 paces, for all of which it ran underground, no doubt for strategic reasons; and it is sixth in order of level. But the cippi of Augustus seem to make the length even greater (8 kilometres against 63.7), and the line may have been shortened in Frontinus' day (i. 18). It was repaired by Q. Marcius Rex (see AQUA MARCIA), by Agrippa in 33 B.C., and by Augustus in 11-4 B.C. It acquired the name of Vetus when the Anio Novus was built. Frontinus found the amount of water at the intake to be 4398 quinariae, or 182,5cubic metres in 24 hours.

We have several cippi of Augustus, some of which, together with a long stretch of its channel going northwards from the porta Esquilina, have been found within the city; the reckoning, as usual, beginning from Rome; and also the inscription of an aquarius aquae Anionis veteris castelli viae Latinae contra dracones.

The original subterranean channel has been found and destroyed just inside the Porta Maggiore; the intrados was at 46.m. above sea-level. Less than two miles from the city, a part of it was turned into the specus Octavianus, which reached the district of the VIA NOVA near the HORTI ASINIANI q.v. The channel is believed to have been identified at various points; but the site of the via Nova is unfortunately quite uncertain. Lanciani believes that it crossed the via Appia by the real (not the so-called) Arch of Drusus, near the vicus Drusianus (see AQUA DRUSIA).

As a result of Frontinus' reforms the turbid water of the Anio Vetus was largely used for watering gardens and for the meaner uses of the city.

|

|

|

|

|

1 - 35 ATONINUS, TEMPLUM. (DIVUS MARCUS, TEMPLUM).

| A temple of Marcus Aurelius which probably stood just west of his column , in the same relation to it as the temple of Trajan to his column. It was erected to the deified emperor by the senate, and is mentioned only once afterwards. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 36 ANTONINUS ET FAUSTINA, TEMPLUM.

| the temple built by Antoninus Pius on the north side of the Sacra via at the entrance to the forum, just wast of the basilica Aemilia, in honour of his deified wife, the empress Faustina, who died in 141 A.D. After the death of Antoninus himself in 16the temple was dedicated to both together. The inscription on the architrave records the first dedication, and that added afterwards on the frieze records the econd. In onsequence of this double dedication the proper name of the temple was templum d. Antonini et d. Faustinae, but it was also called templum Faustinae and templum d. Pii. It is represented on coins of Faustina.

In the seventh or eighth century this temple, apparently in good condition, was converted into the church of S. Lorenzo in Miranda, the floor of which is about metres above the ancient level. Excavations in front of the temple were undertaken in 1546, and in 1899 and following years, when the whole eastern side was exposed to view. It was hexastyle prostyle, with two columns on each side, besides those at the corners, and pilasters in antis. The columns are of cipollino, metres high and 1.45 in diameter at the base, with Corinthian capitals of white marble, and support an entablature of white marble which probably encircled the whole building. The existing remains consist of portions of the cella wall of peperino, built into the walls of the church, extending for 20 metres on the north-west and on the south-east side; the columns of the pronaos, which stand free from the church with the exception of the two nearest the antae; the architrave and frieze of the facade and sides as far as the cella wall extends, but only a small part of the cornice; and the wide flight of steps leading down to the Sacra via, in the middle of which are the remains of an altar. Some fragments of a colossal male and female statue, and a few other pieces of sculpture, have been found. The whole temple was covered with slabs of marble, which have disappeared. The frieze on the sides of the temple was beautifully sculptured in relief with garlands, sacrificial instruments and griffins, and on the columns are numerous inscriptions and figures, some of which are Christian and have been scratched as early as the fourth century A.D. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 37 ANTRUM (Notitia). ATRIUM (Curiosum) CYCLOPIS.

| mentioned only in the Regionary Catalogue (Region I), was probably a grotto in the side of the hill, above the VALLIS CAMENARUM . While it is not possible to decide with certainty between these two readings, antrum is probably correct, and this grotto may possibly be the antrum Volcani of Juvenal. The antrum Cyclopis gave its name to a vicus Cyclopis (CIL vi. 2226), which may have extended south-west to the via Appia. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 38 ἈΦΡΔΙΣΙΟΝ:

| apparently a shrine of Venus on the Palatine, mentioned only once, under date of 193 A.D. It is possible, but not very probable, that the name Venus Palatina, given in jest to L. Crassus may be based on the existence of this shrine. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 39 APOLLINARE.

| A precinct in the prata Flaminia, sacred to Apollo, where the first temple to this divinity was dedicated in 431 B.C. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 40 APOLLO, AEDES.

| The first temple of Apollo in Rome, in the campus Martius, vowed in 433 B.C. because of a plague that had raged in the city, and dedicated in 431 by the consul Cn. Julius. It was in or close to an earlier cult centre of the god, the APOLLINAR , either a grove or altar. This was the only temple of Apollo in Rome until Augustus built that on the Palatine, and being a foreign cult was outside the pomerium. Therefore it was a regular place for extra-pomerial meetings of the senate.

The site is variously described as extra portam Carmentalem inter forum holitorium etcircum Flaminium, in pratis Flaminiis near the forum, near the Capitol, near the theatre of Marcellus. These indications point definitely to a site just north of the theatre of Marcellus and east of the porticus Octaviae, on the street that led through the porta Carmentalis to the campus Martius, a little south of the present Piazza Campitelli.

Twice Pliny speaks of works of art in the temple of Apollo Sosianus, and this epithet is usually explained as referring to a restoration of this temple, carried out by a Sosius, probably C. Sosius, consul in 32 B.C. and governor of Syria. Livy's statement (353 B.C.) muris turribusque reficiendis consumptum et aedes Apollinis dedicataest) may refer to an earlier restoration, as the direct evidence of Asconius precludes the possibility of any second temple. This temple was also known as that of Apollo Medicus, and in 179 B.C. the censors let the contract for building a porticus from it to the Tiber, behind the temple of Spes. The MSS. read etpost Spei ad Tiberim aedem Apollinis Medici, which Frank prefers-see below). In Greek it appears as Ἀπολλώνιον. The shedding of tears for three days by the statue of Apollo, undoubtedly that in this temple, is cited among the prodigia at the death of the Younger Scipio.

In this temple were some famous works of art, brought probably for the most part to Rome by C. Sosius-paintings by Aristides of Thebes, several statues by Philiscus of Rhodes, an Apollo citharoedus by Timarchides, a statue of Apollo of cedar wood from Seleucia, and the celebrated group of the Niobids, which even the ancients were doubtful whether they should ascribe to Scopas or Praxiteles. The day of dedication of the temple in the Augustan period was 23rd September. Below the cloisters of S. Maria in Campitelli are remains of its podium wall, metres long, over 4 high and over 2 thick. Delbruck assumed without question that it was a part of the original structure; but Frank, while admitting that the core, of blocks of cappellaccio tufa, may belong to it, maintains, owing to the use in the facing of tufa from Monte Verde (the southern end of the Janiculum) that the rest belongs to the restoration of 179 A.D., except some concrete with facing of opus reticulatum, attributable to the restoration of Sosius. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 41 APOLLO ARGENTEUS.

|

|

|

|

1 - 42 APOLLO CAELISPEX.

| A monument, undoubtedly a statue, in Region XI, mentioned only in the Regionary Catalogue. It probably stood between the forum Boarium and the porta Trigemina. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 43 APOLLO PALATINUS, AEDES.

| The second and far the most famous temple of Apollo in Rome, on the Palatine within the pomerium, on ground that had been struck by lightning and therefore made public property. It was vowed by Augustus in 36 B.C. during his campaign against Sextus Pompeius, begun in the same year, and dedicated 9th October, B.C. 28; probably represented on a coin of Caligula (see also DIVUS AUGUSTUS, TEMPLUM).

This temple was the most magnificent of Augustus' buildings, constructed of solid blocks of white Luna le, probably either prostyle hexastyle or peripteral and octastyle. The intercolumnar space was equal to thrice the diameter of the columns; on the roof was a chariot of the sun and statues by Bupalos and Athenis; and the doors were decorated with reliefs in ivory, one representing the rescue of Delphi from the Celts, and the other the fate of the Niobids. Before the entrance to the temple stood a marble statue of the god, and an altar surrounded by four oxen by Myron In the cella was a statue of Apollo by Scopas, one of Diana by Timotheus, and of Latona by Cephisodotus. Itis uncertain whether Propertius' distich.

refers to these statues in the cella, or to the relief in the pediment. Golden gifts were deposited in the temple by Augustus (Mon. Anc. xxiv. 54) and it contained a collection of seal rings and jewels (dactyliotheca) dedicated by Marcellus, hanging lamps, and a statue of Apollo Comaeus, brought to Rome in the time of Verus.

For a possible representation of the statue of Apollo Actius, see ARCUS CONSTANTINI.

The temple was connected with, and perhaps surrounded by, a porticus with columns of giallo antico, between which were statues of the fifty daughters of Danaus and before them equestrian statues of their unfortunate husbands, the sons of Aegyptus. It is possible that the ARCUS OCTAVII formed the entrance to this porticus. Adjoining, or perhaps forming a part of the porticus, was a library, bibliotheca Apollinis, consisting of two sections, one for Greek and one for Latin books, with medallion portraits of famous writers on the walls, and large enough for meetings of the senate. The space enclosed within the porticus was the area Apollinis, or area aedis Apollinis.

The Sibylline books were brought here from the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol and placed beneath the pedestal of the statue of Apollo, and they were saved when the temple itself was burned. Part of the ceremony of the ludi saeculares took place at this temple, and it is mentioned incidentally by Tacitus and in Hist. Aug. Claud. 4 in connection with a meeting of the senate. It is mentioned in the Notitia (Reg. X), but was burned down on 18th March, 363 Besides Palatinus, the usual epithet of the god worshipped in this temple we find navalis, Actius, Actiacus, and Rhamnusius.

The facade of the original temple was Ionic, if Richmond cit. is right; while it was restored in the Corinthian order by Domitian, if a relief in the Uffizi is correctly interpreted.

The site of the temple has been much discussed. Three main theories have been brought forward, according to which it should be placed (a) in the garden of the Villa Mills; (b) in the area of the so-called Vigna Barberini, the centre of which is occupied by the old church of S. Maria in Pallara or S. Sebastiano (for the Regio Palladii or Pallaria see DOMUS AUGUSTIANA,p. 165); (c) to the south of the DOMUS AUGUSTI , facing over the circus Maximus, being identified with what is generally known as the temple of JUPITER VICTOR or PROPUGNATOR .

(a) The first theory may be dismissed briefly. The further study of the fragments of the forma Urbis and the progress of the excavations have shown that there cannot possibly have been room for the temple and area of Apollo in the garden to the north-east of the actual Villa Mills.

(b) The second theory, which is that of Hulsen, is apparently more in accordance with some of the literary testimony than the third. At present we do not know what this area contains; and all that is to be seen belongs to the time of Domitian. The temple was burnt down in 363, it is true; but it is only to be expected that some remains of it exist; and the question could be settled by a few days' excavation.

(c) The third theory is on the whole the most satisfactory. What remains of the temple is a podium of concrete of the Augustan period, with a long flight of steps, facing south-west. This has been recently cleared, but no report has been published. On the south-east part of it is built over the mosaic pavements of a room and the cement floor of an open tank of a house of a very slightly earlier period (perhaps the domus Palatina, a part of which was destroyed for the erection of the temple). A hypocaust on the south-west, five tiles of which bear the stamp. 1 belonging to another (?) house in front of the temple, has been demolished to give place to the steps, and vaulted substructions of this house may be seen below on the face of the hill. It is very difficult to think of any other temple but that of Apollo for the erection of which such a house would have been demolished. See Parker, Historical Photographs, 2794. It is, too, certainly a strong argument for the contiguity of the temple of Apollo and the house of Hortensius that the temple site was apparently brought for an extension of this house.

Another point is the rough identification of both in the Augustan age with the site of Romulus' hut and Evander's citadel, both of which stood on the south-west side of the hill.

It seems, too, that the Carmen Saeculare, sung from the steps of the temple, would have far more point were the temple of Diana visible on the Aventine opposite, with those of Fides on the Capitol, and of Honos and Virtus near the porta Capena (both of which are named in it) also within view.

On the other hand, the passages in regard to ROMA QUADRATA, etc. are certainly much more difficult to interpret. There is little room for the area Palatina in front of the temple; and the attempt to make it face north-east will not hold with the remains themselves. Remains of a part of the portico may be identified under the Flavian domus Augustiana: while the libraries, if correctly identified with the two apsidal halls to the south-west of the triclinium of that house, must have been entirely reconstructed by Domitian. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 44 APOLLO SANDALIARIUS.

|

|

|

|

1 - 45 APOLLO, TEMPLUM.

|

|

|

|

1 - 46 APOLLO TORTOR.

| a shrine (?) somewhere in Rome, probably of Apollo as the flayer of Marsyas, where the words "dorthin aus Rom verschleppt" show that the author is not aware that S. Eusebio is in Rome-but Hulsen, who is inclined to accept the identification with Apollo Sandaliarius, believes the words quoted to be a gloss, or as the punisher of slaves. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 47 APPIADES.

| a fountain in front of the temple of Venus Genetrix in the forum Iulium. In two passages Ovid speaks of one Appias, and in one passage of Appiades, whence it is to be inferred that several statues of Appias, probably a water nymph, surrounded the fountain. Pliny states that Asinius Pollio had a statue of the Appiades by Stephanus, and this may have been a copy of that in the forum Iulium. The name has not yet been explained, as the aqua Appia did not extend to this part of the city. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 48 AQUA ALEXANDRI(A)NA.

| * an aqueduct which takes its name from its con- structor, Alexander Severus. It seems to be referred to as forma Iovi in a document of 993 A.D.

The springs were used by Sixtus V for the Acqua Felice (1585-7), but the whole course of the aqueduct was only identified in the seventeenth century by Fabretti, whose accurate description of its interesting remains is followed by LA 380-393 ; LR 56. Its course from the third mile of the via Labicana towards the city is quite uncertain, and the 'nymphaeum Alexandri,' the so-called 'trofei di Mario,' is the terminal fountain of the AQUA IULIA ; though the piscina of the Vigna Conti, generally attributed to the THERMAE HELENIANAE , may have belonged to it. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 49 AQUA ALSIETINA.

| an aqueduct constructed by Augustus (and therefore also called Augusta), which drew its supply from the lacus Alsietinus (Lago di Martignano), with some additions near Careiae (Galera) from the lacus Sabatinus, 6 miles to the right of the fourteenth mile of the via Clodia. It was 22,172 paces long, of which 358 were on arches. Its supply was only 392 quinariae, all of which was used outside the city. The quality of the water was indeed so bad that it was probably intended mainly for the NAUMACHIA AUGUSTI , behind which it ended, the surplus being used for gardens and irrigation, except when the bridges were under repair, and it was the only supply available for the Transtiberine region. Frontinus' statement that in level it was the lowest of all requires qualification. A portion of its channel has recently been discovered to the south of that of the AQUA TRAIANA, and at a considerably lower level. The identification of its channel and terminal castellum with the remains described by Bartoli, which lay a good deal further to the north, below Tasso's oak, must therefore be given up. The aqueduct is referred to in an inscrip- tion of Augustus, which mentions formam Mentis attributam rivo Aquae Augustae quaepervenit in nemus Caesarum. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 50 AQUA ANNIA

| An aqueduct mentioned in Not. app.; Pol. As both the Anio Vetus and Novus are omitted in the list, it is probable that this is a corruption, especially as we have no other knowledge of an aqua Annia; and the same applies to the AQUA ATTICA, which is also found in the list. |

|

|

|

|

1 - 51 AQUA ANTONINIANA. (AQUA MARCIA).

| constructed in 144-140 B.C. by Q. Marcius Rex, the water being brought to the Capitol in the latter year. He had been commissioned by the senate to repair the Appia and Anio. The total cost was 180,000,000 sesterces or £1,800,000 sterling.

Two arches of this aqueduct may be represented on a coin of C. Marcius Censorinus, and five arches on coins of L. Marcius Philippus.

It was repaired by Agrippa in 33 B.C. and again by Augustus, with the rest of the aqueducts, between and 4 B.C. Rivos aquarum omnium refecit, in the inscription of the latter year on the monumental arch by which it was carried over the via Tiburtina, later incorporated in the Aurelian wall as part of the PORTA TIBURTINA.